A Novel

Verlag Braumüller 2010

In Vienna, a secret cult brings forth strange fruit: the Ariosophists. Masked and disguised, the cream of society, including high-ranking Nazis, meets in the headmaster Panigl’s salon. While they invoke maintaining the purity of the Aryan race, they indulge in bizarre sexual rituals. Intoxicated with a drug, the young inexperienced teacher Pola Wolf takes part in the “magical soirée–and misfortune takes its course.

In 1937, Pola Wolf is standing trial for poisoning. It was mere luck that allowed Panigl and his wife to survive three perfidious attempts at murder. The background of the case is not mentioned during the trial. Pola’s motive remains unexplained.

Only after the end of the war in 1945 does she again take up the trail leading to Panigl…

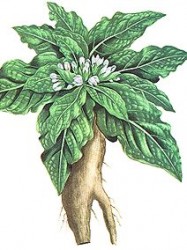

MANDRAGORA, also known as mandrake or mandegloire. The “queen of all magic herbs.” Because of the humanlike shape of its roots, this plant has drawn people’s attention since early times. The meaning Mandragora (= love herb), from the Persian, points to its frequent use as an aphrodisiac in ancient times. It is supposed to bring luck, and it is one of the most important ingredients for witchcraft and magic rituals. The root has narcotic and hallucinogenic effects. High dosages can cause death by respiratory paralysis.

The cold was eating away at her toes. It rose up like an icy river that was lifting her from her bed and pulling her down into its shimmering depths, so exquisitely frosty. She reached out her hands, trying to hold fast, but instead of the wooden bedpost she felt only the slipperiness of ice floes. Even the tears in her eyes were frozen, round, transparent spheres in which the light from the depths danced. A voice far above, distant and plaintive, sang a song whose words she did not understand. A foreign language. Mother’s voice. Her heart grew lighter. She did not have to resist. Only surrender to the current. Embrace the cold.

“Please! Can’t you hear? For God’s sake!”

She wanted to shut her ears. She did not belong here. She could not fulfill any entreaties. She was already gone. But then she started to feel her cramped, clenched fingers and the bedspread that they held in their grip. After the storm there had been a change in the weather. The night wind blew through the broken windowpane. The pasteboard that was supposed to seal the window was loose, clattering and knocking at every gust of wind. If she kept sleeping, she would arrive down below, sinking to the bottom between the bright stones, letting herself be borne away by the current, to the other side, where they were waiting? So many of them. With their mutilations that no longer caused any pain.

There was that voice again, high and plaintive, and a hand jiggling the doorlatch. Pola rose up. Her toes were stiff with cold, yet her feet carried her. She opened the door. The woman came inside and slammed the door behind her. It was no longer totally dark in the room. In amazement, Pola recognized Luise.

“I was starting to worry you wouldn’t open up.” Luise sounded apprehensive.

“I often hear you at night, but today–what’s the matter? Bad dreams?” She laid a hand on Pola’s arm. “I suddenly had the feeling you ought not to be alone.”

Pola got back in her bed. The blanket was a piece of old curtain material that didn’t keep her warm. Luise followed her. “Is it all right with you if I stay?”

Pola shifted a bit to the side. She left a piece of blanket for Luise. She still hadn’t said a word. She wasn’t able to. They sat very close to each other. A smell rose from Luise’s clothes, something fresh, a little sweet, a little tart.

“Thank you,” said Luise.

Suddenly she sank back into Pola’s pillow, and Pola followed her example, immersing herself in the warmth and softness, the delicate fragrance of a perfume. Why has she come, she thought, and then nothing more.

That’s how they slept until Herr Karner next door started coughing and clearing his throat, the morning ritual with which he began his day.

Pola woke up earlier than Luise. She thought of the icy river that had carried her through the night. If it had continued, Luise wouldn’t have woken her. If dying was so easy, why did they all fight so bitterly to stay alive? It had been cold there. No place had ever been so cold. Her body could remember. Now she would be ashes on the leaves of the trees, on the fields, wherever the wind carried her, far away in the east, laid down to rest where the wind took a rest, was she there too? And the child?

The blond woman’s forehead was flawless, like a child’s, her neck smooth and white, her lips closed as gently as if they knew no angry words. Luise had plucked her eyebrows down to a high arch, which lent her a surprised and joyful look, even in sleep. Her eyelashes were long and thick, quite light, like her hair.

Under Pola’s scrutiny, Luise began to move. A twitch passed across her forehead. She opened her eyes and stared at Pola. The blue of the sea, which Pola had never seen: that is how it must have been, off the coast of Montenegro, where Nadija had spent her childhood summers. Dark blue and green and translucent down to the bottom, golden and blue at the shore, in the sunshine, when the rocks cast their shadows, silvery gray in the moonshine. The sea in Nadija’s memory was like a poem. Luise returned her gaze, calm and alert. What did Luise see? In her eyes Pola did not make out a single spark of the disgust and alarm that the young woman must have felt at the sight of her.

“Good morning,” said Pola.

Luise smiled, still sleepy. Embracing like a pair of lovers, they lay on the narrow ottoman in Herr Karner’s living room.

“I will not forget this night.” She kissed Pola on the cheek.