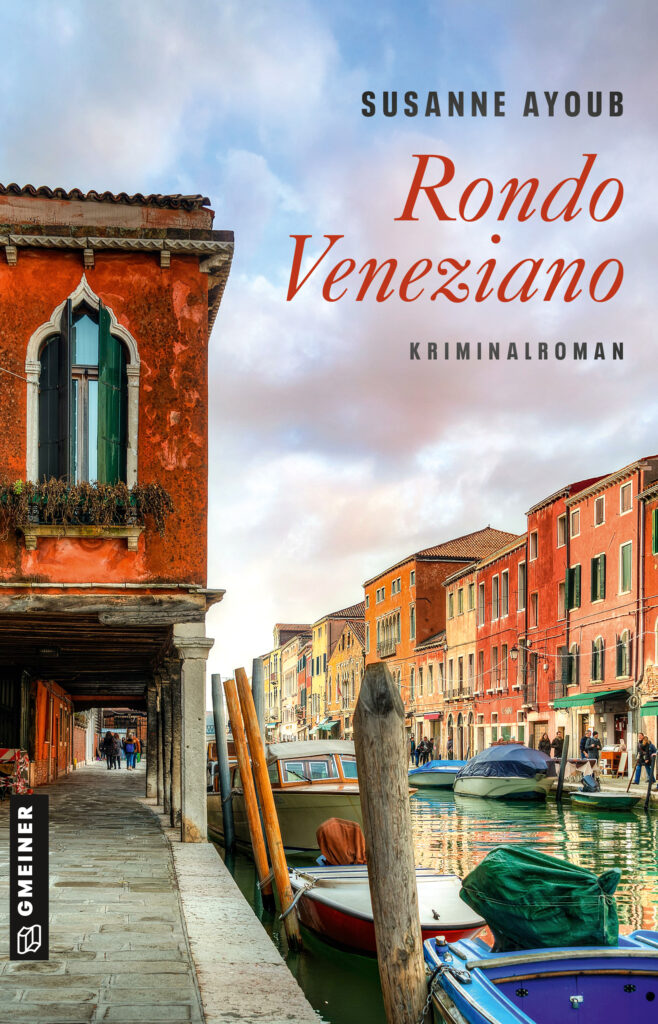

The audiobook version of my first novel, “Angel’s Venom,” is available again, reissued by the Danish publishing house Saga Egmont (Copenhagen 2021).

Poverty is the pinch of shoes that are too tight because children’s feet grow so quickly. Poverty is being sick without medicine because the doctor’s fees are unaffordable.

Poverty is soup kitchen fare, a seat at a table in a charitable shelter where the needy sleep sitting up. They have no bed. Poverty is the glad feeling in frozen fingertips warming by a fire on a cold winter night. Poverty is a pauper’s grave.

Poverty is where romanticism has no home, only pain and dark rage against the others who have everything and keep it from you, as if you didn’t have the same right as they have to survive.

“As a young girl I liked to imagine what it would be like to be poor. Really poor, like in The Little Matchstick Girl, Hansel and Gretel, or The Star Money, freezing and hungry and all alone in the world,” Marie Horvath says. She can imagine the child with bare feet in oversized clogs, but not that this child owned no other shoes.

I rewind the thread of fate, from me back to Karoline, to her beginnings, which themselves are nothing but a continuation. Lotte Loew, at the window in the signalman’s hut, dreaming like the mute husband over his postage stamps, two disillusioned people at my mother’s cradle. They too deserve my attention, they too had their reasons, their motivations, they too carried on. The ball of blame is tossed backwards from generation to generation, until the trail gets lost in the past, in faceless ancestors. In the artfully fashioned mesh, interwoven by encounters and circumstances, torn, knotted, and patched, I seek out my story. And Marie Horvath, that child of her times, listens, intent yet impatient, because I distance myself farther and farther from what she calls the essence, the story, the scandal, from Karoline’s unimaginable transgression.

****************************************************************

That Kritsch had taken Karoline in like a daughter of his own was no empty phrase. In the evening, behind locked doors, he made her dress in little girl’s clothes. He plaited her long hair into braids and hung a schoolbag on her back. Then he fumbled in her panties, growing aroused by her resistance, feigned or unfeigned. Everyone knew about it, no one cared about it. Karoline herself seemed content with her situation.

“He wanted to educate and raise her, to make her into a proper young woman who could move in his social circles, sit at our table as our coequal. But of course that was out of the question. We really thought that was going too far.”

“Get to the point, Herr Kritsch.” The examining magistrate rapped impatiently on the thick dossier on his desk. “Do you have anything to say that will help solve this crime? I have sent for the old autopsy report. Moritz Kritsch was seventy. High blood pressure, hardened arteries, overweight, cause of death brain stroke. The report leaves no doubt that your father died a natural death.”

“He had just taken out life insurance with her as the beneficiary! Doesn’t that sound familiar to you, Herr Councilor? And no one became suspicious in these cases, neither the aunt nor the lodger woman, isn’t that right?” Johann Kritsch leaned in conspiratorially toward the judge. “I know it wasn’t poison, that was settled clearly at the time. But she drove him to his death, she goaded him and provoked him until she blew out the flame of his life, just as if she had laid hands on him herself! That’s what a cold-blooded criminal she is!”

“Prepare yourself for the end,” the doctor said. That night, Karoline had hastily called him to her husband’s sickbed. “There is no more hope.” Karoline was still wearing the schoolgirl’s dress she’d put on for Kritsch, the short little skirt with the white lace panties under it that were open at the crotch, exposing her red pubic hair when she bent over. “You’re sick. The doctor says you need rest,” she’d protested. “Drink your bouillon, you promised you would, Kritsch.”

But he didn’t feel like soup, he felt the end approaching and clung to life with his last bit of strength. “Just once more, to make me happy. Do it for me, my love,” he begged, and so Karoline slipped reluctantly into the tight-fitting children’s clothes and showed him her backside. He reached between her white thighs, except this time it was no longer desire that made him pant and gasp, but death, which pressed on his heart with its broad, implacable hand. Karoline ran, dressed as she was, to get help, and in her fright she didn’t even notice the doctor’s leer. She knelt next to Kritsch’s bed and laid her head on his enfeebled hand.

“Don’t leave me, how can I live without you, come back, Kritsch, darling, my beloved husband!”

The doctor made a snide face at this performance. Like everyone else, he knew that Karoline was merely lying in wait for the old man to die. No one felt sorry for him, he was just reaping what he’d sown. Karoline’s extravagance, her greed for jewelry and clothes and furs, which grew with every year, would have ruined Kritsch if only he’d had enough time left.

****************************************************************

Pain seized Karoline. It ran along her spine, pierced her muscles and tender fatty tissue, burrowed into the coils of her intestines, and eventually flooded her whole body. As this wave ebbed away, because the obstacle she was trying so violently to push into the light would not budge, she whimpered, weak and relieved. The stars twitched in the sky above her head. A dress rustled by her ear, a hand wiped the sweat from her brow. She smelled vinegar, which was supposed to refresh her temples, and disinfectant soap on the hand that pressed the sponge against her face. The blanket covering her tortured body was pulled off. She winced at the skillful fingers that were poking her, fumbling, probing. They awakened the pain that had been waiting for this moment and now bit into her flesh with a thousand teeth.

“No,” she cried. “Not again. I can’t take anymore!” But the great flood was already in her, breaking against the obstacle, straining and tearing at her. She heard a siren’s sound, strange and shrill, which broke off at its peak and sank back into a breathlessly strangling gurgle: her own voice. “Just breathe calmly. Deep breaths, in and out. Don’t cry, that will only sap your energy.”

Then there was no more breath, only a raging sun in her viscera, igniting a huge fire, scorching her, burning her up. The wave no longer pushed outward, it thrashed back and forth, setting the obstacle in motion, the great solar orb itself. The obstacle, the infernal agony, the child. Her son. Me.

English translation by Geoffrey C. Howes

The festival will commence this Saturday and run until April 19, in the ancient city of Babylon, featuring participation from Qatar alongside prominent intellectuals, writers, artists, and musicians from Iraq, the Arab world, and internationally.

The festival will commence this Saturday and run until April 19, in the ancient city of Babylon, featuring participation from Qatar alongside prominent intellectuals, writers, artists, and musicians from Iraq, the Arab world, and internationally.

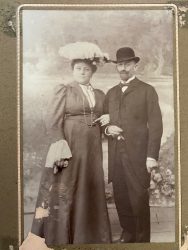

Dämmerlicht. Langsam wird es heller. Die Konturen eines Wohnzimmers zeichnen sich ab. Ein Foto an der Wand wird allmählich sichtbar. Ein Paar. Altes Schwarzweißbild, vergilbtes, gelbliches Papier. Ein Hochzeitspaar. Meine Eltern. Meine Mutter hat in Schwarz geheiratet.“

Dämmerlicht. Langsam wird es heller. Die Konturen eines Wohnzimmers zeichnen sich ab. Ein Foto an der Wand wird allmählich sichtbar. Ein Paar. Altes Schwarzweißbild, vergilbtes, gelbliches Papier. Ein Hochzeitspaar. Meine Eltern. Meine Mutter hat in Schwarz geheiratet.“

Saturday, November 18, 2023

Saturday, November 18, 2023

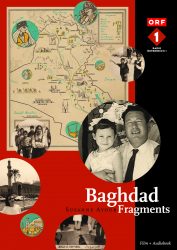

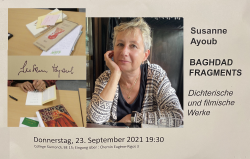

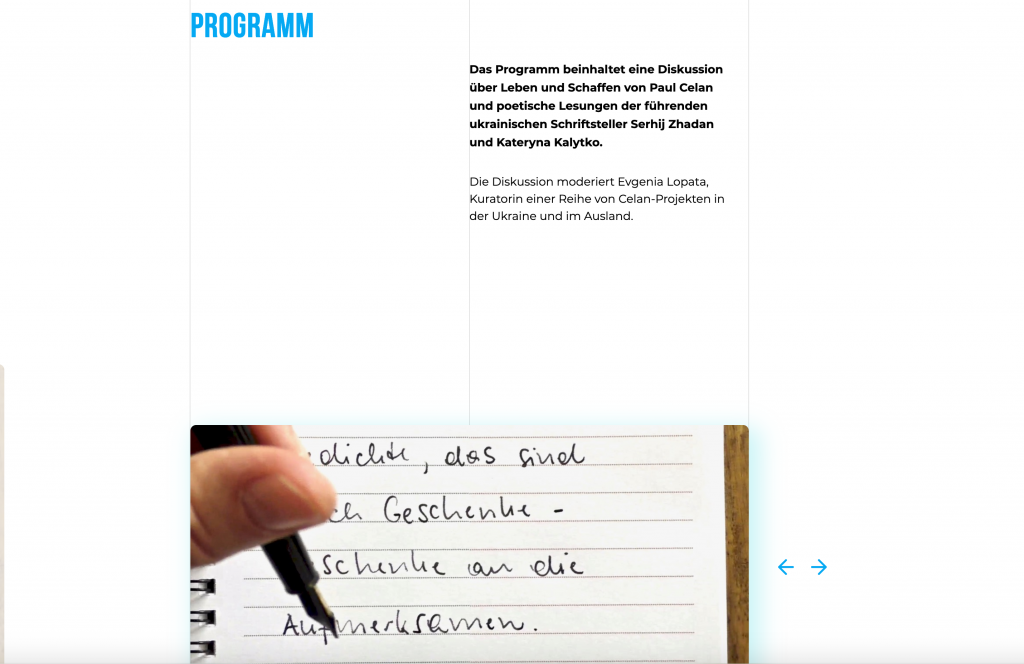

OE1 Kunstsonntag (Arts’ Sunday) New Texts:

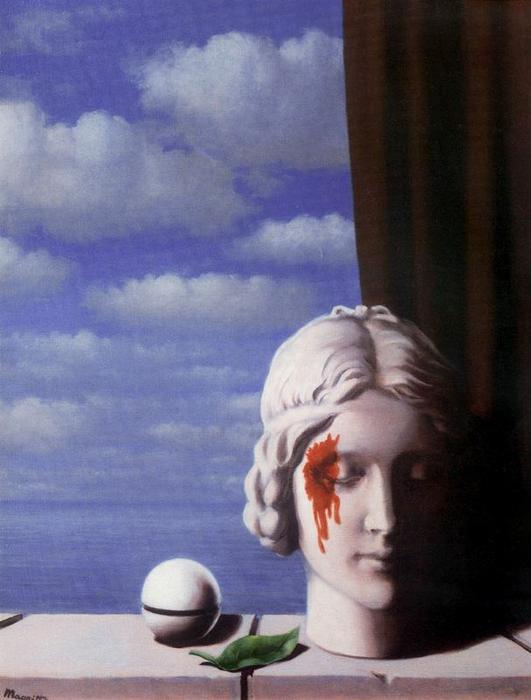

OE1 Kunstsonntag (Arts’ Sunday) New Texts: “The similitude, the most important criterium in portraiture, was there: the beautiful, regular features, the gentle, restrained gaze, the pensive mouth. And then it suddenly morphed into a girl’s face, and every correction only increased that impression. At the last sitting, David saw the bust before John could cover it up. ‘You’ve got to change that,’ he said. ‘My father wouldn’t like it.”

“The similitude, the most important criterium in portraiture, was there: the beautiful, regular features, the gentle, restrained gaze, the pensive mouth. And then it suddenly morphed into a girl’s face, and every correction only increased that impression. At the last sitting, David saw the bust before John could cover it up. ‘You’ve got to change that,’ he said. ‘My father wouldn’t like it.”

SUNDAY, AUGUST 21 3:05-4:00 PM

SUNDAY, AUGUST 21 3:05-4:00 PM

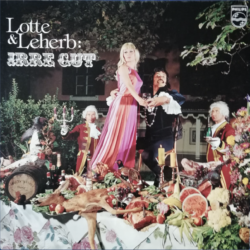

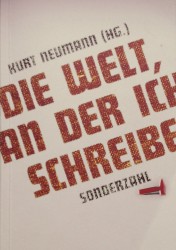

The leitmotif of my story ‘Revolution,’ which appeared in the anthology ‘Die Welt, an der ich schreibe‘ (The World I’m Working on in Words), ed. Kurt Neumann, published by Sonderzahl, 2005.

The leitmotif of my story ‘Revolution,’ which appeared in the anthology ‘Die Welt, an der ich schreibe‘ (The World I’m Working on in Words), ed. Kurt Neumann, published by Sonderzahl, 2005.

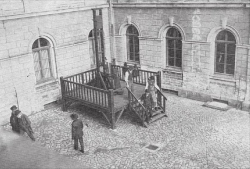

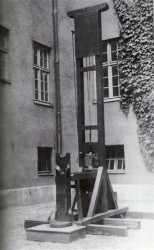

THE MAUTHAUSEN CONCENTRATION CAMP

THE MAUTHAUSEN CONCENTRATION CAMP

The name Käthe Leichter is associated with the golden age of Austrian Social Democracy. Few are still familiar with her life and work. Early on she was committed to improving the education and occupational situation of women. Her studies on women’s work in the First Republic are groundbreaking, and her analyses and demands are disturbingly relevant. In 1934, together with her husband, the journalist Otto Leichter, she founded the Revolutionary Socialists. In 1942, this Jewish resistance fighter was murdered by poison gas in the Bernburg/Saale concentration camp.

The name Käthe Leichter is associated with the golden age of Austrian Social Democracy. Few are still familiar with her life and work. Early on she was committed to improving the education and occupational situation of women. Her studies on women’s work in the First Republic are groundbreaking, and her analyses and demands are disturbingly relevant. In 1934, together with her husband, the journalist Otto Leichter, she founded the Revolutionary Socialists. In 1942, this Jewish resistance fighter was murdered by poison gas in the Bernburg/Saale concentration camp.

now she is

now she is

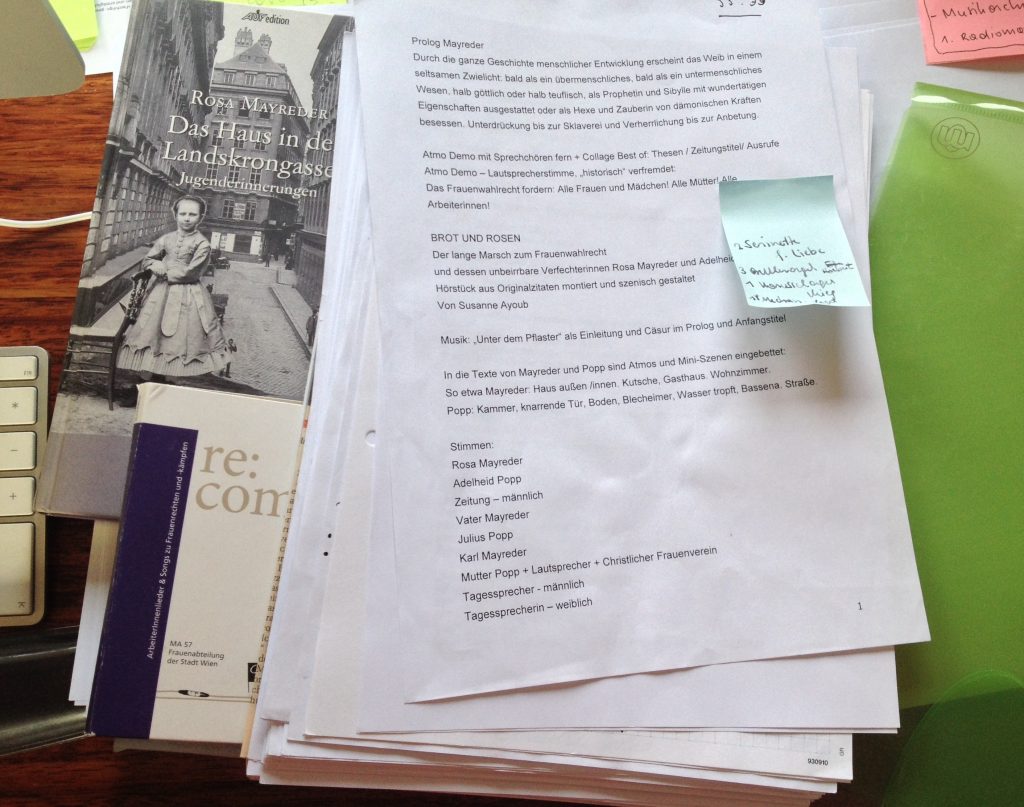

leading there had been long and rough. Susanne Ayoub presents portraits of two of the steadfast champions of a woman’s right to vote in her audio piece “Bread and Roses”: the middle-class writer Rosa Mayreder fought for the education and social recognition of women; the Social Democratic politician Adelheid Popp represented the interests of working women, especially the demand that to this day has not been met: equal pay for equal work.

leading there had been long and rough. Susanne Ayoub presents portraits of two of the steadfast champions of a woman’s right to vote in her audio piece “Bread and Roses”: the middle-class writer Rosa Mayreder fought for the education and social recognition of women; the Social Democratic politician Adelheid Popp represented the interests of working women, especially the demand that to this day has not been met: equal pay for equal work.

Ayoub’s drama combines the story of the theft and the subsequent intensive and often dramatic investigation in the crime with scenes from Caravaggio’s life, his years on the run as a murderer fleeing from the papal ban, until shortly before his death in Sicily, when he paints one of his most moving pictures: the Natività.

Ayoub’s drama combines the story of the theft and the subsequent intensive and often dramatic investigation in the crime with scenes from Caravaggio’s life, his years on the run as a murderer fleeing from the papal ban, until shortly before his death in Sicily, when he paints one of his most moving pictures: the Natività.

There were only a few steps between her and her house when her eyes lit on a bright red spot, right by the curb. She bent down and found the lost playing card. The queen of hearts was in the company of the jack of spades. She called out after him. This time her voice was clear, but it was drowned out by a passing car. Steel-spoked wheels jolted over the old cobblestones. She drew the key from her coat pocket and was going to unlock the front door when she bumped into rough stone. There was no door there. There was no house.

There were only a few steps between her and her house when her eyes lit on a bright red spot, right by the curb. She bent down and found the lost playing card. The queen of hearts was in the company of the jack of spades. She called out after him. This time her voice was clear, but it was drowned out by a passing car. Steel-spoked wheels jolted over the old cobblestones. She drew the key from her coat pocket and was going to unlock the front door when she bumped into rough stone. There was no door there. There was no house.

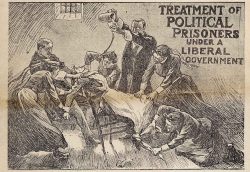

Let us recall this statement: “The father is not related to his illegitimate child.” Who could have ever come up with this monstrous mockery of all natural and honorable feelings?

Let us recall this statement: “The father is not related to his illegitimate child.” Who could have ever come up with this monstrous mockery of all natural and honorable feelings?

well fed and well dressed

well fed and well dressed wasn’t believed

wasn’t believed